The Coronavirus caught the world off guard, and for the first time in her life, undefeated boxing world champion Michele Aboro was hit with a punch she didn’t see coming.

Aboro’s wife, Masca Yuen, left Shanghai, where the pair owns the boxing gym Aboro Academy, on January 23rd. She was headed south, to Schenzen, with their 2-year-old daughter, Blue Stella, to celebrate the Lunar New Year with her family. Shortly after, a neighbor there was diagnosed with COVID-19, and Yuen and Blue were forced to evacuate to Hong Kong. China’s borders closed. The weeks turned into months. Blue turned three and outgrew all the clothes she had with her. She started school in Hong Kong and learned to suck on a lollipop through her mask, while Yuen did Tabata workouts at the skate park near her sister’s apartment where they were staying. Aboro underwent her 12th round of chemo for breast cancer while working long hours to keep the gym clean and afloat. Each day, the family, separated by 800 miles and a sliver of the South China sea, convened on Zoom to relay the events of their separate but connected lives while Aboro battled to also keep the Aboro Academy family together.

It was a full 10 months before Yuen and Blue were able to return to China. There, Aboro, as ever and despite the odds, was still strong on her feet.

Fighting To Fight

Aboro, now 52, was born in Hammersmith, West London, one of seven children raised by a single mother. “We’re Irish, Scottish, and African,” Aboro says. “From a young age, we were picked on because of our color, and because my mom was a white woman with all these black children. We grew up to have a thick skin, and I learned to take in the negativity and push it out with positivity.”

Aboro first discovered boxing at the age of 9, and was told that it was actually illegal for women to box in the United Kingdom because the sport was considered unladylike. “I grew up in a very open family and we were never told we couldn’t do something because we were a boy or a girl,” Aboro recalls. “That was the first time I realized girls and boys are not treated the same, and it can be problematic if you’re a girl.” So, she found another way to get into the ring: kickboxing, which ironically, was legal.

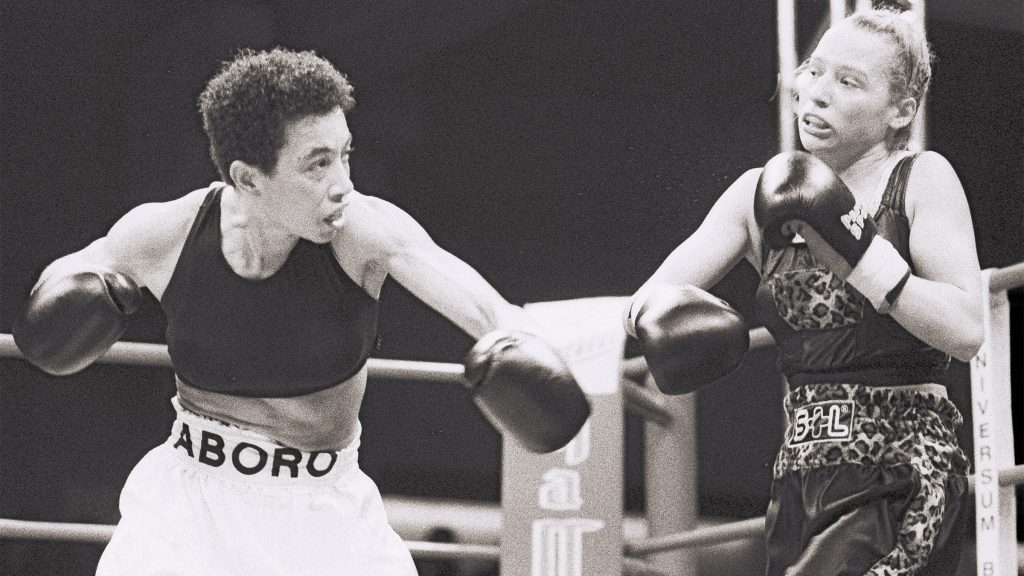

Aboro started with karate and judo, then began training at the age of 16 with muay thai master Lincoln Boney. She went on to win five British, one European and three World Champion kickboxing titles, all while training in boxing on the side to have an advantage over her kickboxing opponents. Finally, in 1995 at the age of 27, Aboro got a work contract in Germany and was able to enter the world of professional boxing. And from then on, she never lost a fight.

During her seven-year professional boxing career, Aboro posted a record of 21 wins – 12 by knockout – and zero losses. She won the Women’s International Boxing Federation super bantamweight (118 – 122lbs) world title in 2000 and defended it three times against former world champs like Nadia Debres, Daisy Lang, Eva Jones and Kelsey Jeffries. When Aboro retired in 2002, she had been voted the best “pound for pound” female boxer in the world for four consecutive years.

“I’m proud I managed to retire undefeated,” Aboro says. “I’m proud I was able to get to the level I did in a country I wasn’t born in. I’m proud of my achievements at a time when women weren’t recognized as boxers. Today, I’m delighted to see women’s boxing in the Olympics and big promoters signing female athletes. More and more women are getting a platform and using it to highlight what they’re capable of.”

From Athlete To Coach

After her retirement from boxing, Aboro was living in Amsterdam, working the door at Club Paradise, where she befriended the head sound engineer. He encouraged her to pursue a career in sound engineering, and Aboro, who loves music and had played the bass guitar for a long time, liked the idea. She went back to school, then worked for eight years for musicians Joan as Police Woman, The White Stripes and Amy Winehouse. It was during that time, in 2009, that Aboro and Yuen, who is Chinese but was born in Eindhoven, Holland, began dating. It was Yuen who first pushed Aboro to become a coach, believing she could help mainstream people become healthier and more confident in themselves. After much persuasion, Aboro agreed to coach Yuen and a group of friends in a rented room in Amsterdam.

“I went into sports because I loved to compete, not because I wanted to be a coach,” Aboro says. “Coaching is a skill. It’s not just something you can go do, even if you were a great athlete, and I realized and understood that.” Aboro was concerned that after spending so many years with elite athletes who are very in tune with their bodies and can immediately adapt to any suggestion, working with normal people who are not as coordinated would be frustrating. And, at the beginning, her concerns were somewhat founded.

One evening, Aboro was stressing the importance of keeping the hands up in the ring, while her undisciplined female students chatted away. “So, she punched me in my face,” Yuen recalls. “But it certainly helped everyone to remember, because after that, everyone had their hands up.”

Many of the women Aboro worked with in Holland struggled with depression, anxiety and other mental health issues and Aboro was amazed to see the positive impact boxing had on them. “Boxing broke the cycle for so many of them,” she says. “It made them feel alive and worthwhile, and showed them they could be more than what they thought they could be. I saw how learning to box improved their mindsets and their confidence, and changed the way they looked at themselves, and it gave me goose bumps. I was hooked.”

From Holland To China

Yuen, a fine arts photographer, traveled to China while working on a book about the history of her family. While she was there, Aboro went to visit, and fell in love with the friendly people in the dynamic city of Shanghai. “People use the word ‘metropolis,’ but you’ve never seen a metropolis until you’ve seen Shanghai,” Aboro says. “It will blow your mind.”

On her visit, Aboro could not find a place to train, and got the idea that Shanghai would be a great place to open a gym. But at the time, the couple just did not have the means. So, Aboro began taking clients in other people’s gyms, and also taught a group of women on a downtown Shanghai rooftop for over a year. “Miraculaously, it never rained,” says Yuen.

By 2011, Aboro was managing a gym owned by two other partners. But in 2012, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and took a hard look at the direction of her life. “I looked at the gym I was running and thought, ‘This is not what I want to do,’” Aboro says. “This was not my dream. This was somebody else’s dream, and I was living it for them. We hadn’t come to China to open a gym for somebody else.” So, Aboro and Yuen decided to open a gym of their own.

The Aboro Academy And Aboro Foundation

Aboro and Yuen began working with children as soon as they moved to China, creating the Aboro Foundation with the goal of educating children in sports and fitness. In 2014, the pair opened The Aboro Academy on Changhua Road in Shanghai’s central Jing’an District, known for a diverse array of sites, from an ancient, golden-roofed temple and sculpture park to skyscrapers and dim-sum restaurants. The goal of both is to offer training to athletes of all levels, from those who would be world champions to those who are simply looking to live a healthier lifestyle, in a positive and welcoming environment.

“China is very extreme, and for many, they believe it’s a gold medal or nothing when it comes to athletics,” Aboro says. “We want people to realize you don’t have to be an Olympic star, or even want to be one, to walk into a boxing gym.”

Aboro says that just three to five percent of the athletes at the Academy are interested in being professional boxers; one male member went on to become a World Boxing Organization Asian Champion and a female member became an international World Boxing Confederation Champ. Around 15 percent of members are white-collar workers who occasionally compete in fights, while the vast majority – around 70% – are just normal people who want to be fit, strong and healthy. It is for those people that Aboro and Yuen are working on the Aboro Ranking System, which will allow boxers to graduate from level to level, much like one does with different color belts in karate or jiu-jitsu.

“We will be the first boxing gym to have this kind of progressive system in place,” says Yuen. “Collecting a patch as you move from one level to the next gives both children and adults a huge confidence boost and sense of accomplishment.” They also plan to offer training certifications in The Aboro Method and Aboro Cardio Boxing.

But beyond material marks of achievement, Aboro and Yuen use boxing to teach their students not about their ability to hurt people but their ability to concentrate and exercise at the same time while pushing the boundaries of their potential; for them, it is about the beauty of the disciplines and not the violence. “Boxing has gotten a bad rep for a long, long time, but when you step away from the rink and look at grass roots, this sport can really save lives,” Aboro says. “We are giving boxing and other combat sports a different face.”

An Extended Family

The Aboro Academy website plainly states, “We want Aboro to feel like your second home.” In the six years since its opening, the Academy has become just that for so many; men and women, young and old, from all walks of life. Prior to COVID, the gym had 260 members, and since reopening, even more have come back, for the boxing, the investment in their health and the community, which has become more like a family than anything else. Blue has grown up in the gym, being watched by coaches and other staff members while her mothers work. “She knows boxing, and is very comfortable around people punching each other,” Yuen says.

But more importantly, the people of Aboro Academy are comfortable with each other. Members of all ages and ethnicities cheer each other on in the sparring ring and when they achieve their first pushup or pull-up. They come out in droves to support other members in their club fights, armed with signs and matching t-shirts. Two Aboro Academy members recently got engaged when one filled the ring at Aboro Academy with white balloons and rose petals to propose to the other. And while Aboro underwent her chemotherapy treatment with Masca and Blue stuck in Hong Kong, long-time Academy coach Yi Feng, whom Aboro considers the son she never had, and another employee moved into Aboro’s house to look after her. “As I was going through chemo, our team was there looking out for me and taking care of Aboro Academy when I could not,” Aboro says. “It’s truly beautiful to see the way our tribe take care, support and motivate both each other and us.”

Yuen agrees. “As immigrants, I believe we have a natural way of connecting with people,” she says. “When you are apart from your blood family, you automatically create your own family and community. So when we opened Aboro Academy, it was quite natural for us to interact with our members like our friends and our team like our family.”