On the eve of her 21st birthday in 2001, Emily Harney was ringside photographing her very first professional fight. Then a student at the Art Institute of Boston (AIB, now part of Lesley College), Emily did what she’s done hundreds of times since then – she watched the fighter as he sat in his corner between rounds and photographed what he actually did.

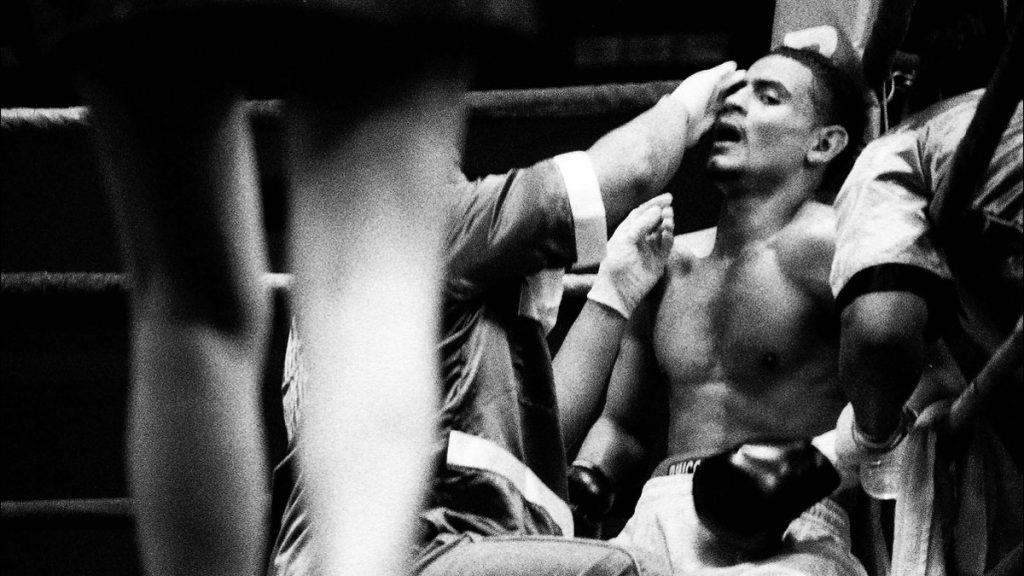

That night, the fighter was Jose LaPorte, and as he sat on the stool in his corner, he allowed his attention to drift from his team and their chatter to what Emily suspects was the round card girl whose legs can be seen in the foreground of the photo. To this day, Emily isn’t sure whether LaPorte was checking the number on the round card or if he was just checking out the round card girl. But that moment, documented for posterity in black and white, is the moment that Emily remembers being pivotal in her decision to pursue boxing photography as a career. She titled the image The Distraction because she said it seemed like LaPorte was just a little distracted for the rest of the fight.

In the two decades that have passed since capturing that distracted glance, Emily has spent countless hours ringside, chronicling the stories of athletes like LaPorte. Hundreds of Emily’s photos have found their way into publications, galleries, newspapers, homes, and social media feeds. Emily is FXQ’s reigning champ for the Best Sports Photo of 2020.

The Artistry of Commercial Photography

When Emily enrolled at AIB in the late 1990s, she had already taken an interest in both boxing and photography. Her uncle introduced her to boxing as a kid and photography evolved naturally from taking pictures of different things in high school, one of which was a football game.

Photographing the live action of a high school sporting event was the catalyst that first nudged Emily toward sports photography as a career choice.

Emily chose to attend the Art Institute as a photography student in lieu of going to a state college and getting on a fine arts academic track. “I figured if I went to a commercial school I wasn’t going to get the push, the critique that I needed to really figure out why [I am] making images,” Emily said in a phone interview. “How do my images resonate, not just with the sports enthusiasts, but with art enthusiasts? I didn’t want my work to be looked at as journalistic. I wanted it to be looked at as more than that.”

The Lesley University College of Art and Design helped Emily to hone her technical skills and refine her documentary style of photography alongside students who were sharpening their own skills as painters, sculptors, illustrators, designers, and visual artists. Emily continued at Lesley University College of Art and Design for graduate school, which provided her access to mentors who were already well-regarded, high-profile artists who were published photographers, curators at The Museum of Modern Art, and artists who had been in residencies at a variety of institutions all over the world.

Going from Student to Storyteller

In October of 2000, a featherweight boxer from Saugus, Massachusetts who fought under the name Bobby Tomasello collapsed in his dressing room after a 10-round bout with Ghanaian boxer Steve Dotse. The story of a hometown guy like Bobby Tomasello, whose real name was Robert Benson, loving a sport so much that he was willing to risk his life to do it captivated Emily.

Tomasello was in a coma for five days before passing away at the age of 24. That event inspired Emily to learn more about the men and women who were willing to risk everything just for a chance to get in the ring. “I really wanted to tell the story of an athlete. An athlete is like an artist. They’re doing what they do for the love of it – it’s not about the money.”

Emily took her first careful steps into the world of amateur and professional boxing by making a phone call to a boxing gym she found in the Yellow Pages. She talked to someone, told the person she was a student looking to photograph boxers, and she was invited to come out to the gym.

It was a 45-minute ride from her house to the gym, but when she arrived, Jimmy Farrell Sr. greeted her with open arms and gave her full run of the place. It was that first introduction to the Farrells (junior and senior) that opened the door for Emily to meet and work with living legends like Micky Ward, Dicky Eklund and Kevin McBride.

Maybe it was her curiosity, or perhaps the fact that she didn’t have an ulterior motive of any kind, that convinced the boxers that Emily wasn’t a threat, though once or twice she was asked if she was a spy. But for the most part, she was made to feel at home. Pretty quickly, she learned that the boxer community is made up of regular guys.

For a time, she worked for boxer Micky Ward. Emily recalls that Ward dug trenches at 6AM before heading to the gym after work to train for his world title fight. “Guys would come to the gym after work. Oh, you have four jobs just like I do. Or this guy’s going to college, too. They were everyday athletes. That made it more humanizing.”

Then there were Emily’s parents, who were understandably concerned about Emily’s decision to work in a field like boxing, where very few women ventured at the time. Emily spent all of her time in gyms and at boxing venues, even traveling to places like New York or Atlantic City to document these fights. But her parents’ trepidation subsided a bit after they attended their first boxing match and discovered many of the boxers Emily spent her time with when she wasn’t actively taking photos were men like her grandfather – well into their senior years and more interested in telling great stories than doing any harm.

Telling the Stories of the Greats

Chronicling the events of a match or capturing the moment when a boxer absorbs the impact of a hit gives Emily a different perspective of the tactical aspects of the sweet science than most onlookers. “You can be a fan in the audience and you see one thing, but as a photographer looking through the lens, I can capture that split second of a hit where the head’s indented before the swelling starts.”

Emily has also been in the ring herself. She trained a full year to fight three two-minute rounds on an all-female card. The event, promoted by Haymakers for Hope, raised more than $600K to donate to different fighter-selected nonprofits. Emily noted that after that year of grinding it out, finding the will to get in the gym, or get out and run in the mornings, she had an even higher level of respect for boxers.

Emily’s experiences over the past 20 years include working for two boxing promoters. “If I had to deal with the business of this all the time, it would make me not love the sport,” she said of working behind the scenes. But the years she spent working to promote fights were also valuable in helping Emily to see how events come together and just how vulnerable boxers truly are.

With respect to professional athletes, boxers lack the protections put in place to protect football, basketball, and hockey players. Many boxers don’t have health insurance beyond what’s provided for them at their jobs. Most times, boxers don’t have the knowledge or the team in place to capitalize on their wins to use them as vehicles for increasing their visibility and opening up more opportunities for them outside the ring.

“If you [market these guys], you could put more money in their pockets without them having to get punched in the face,” Emily says.

That passion which grew from years of working in the boxing community, knowing the boxers, and watching their discipline and commitment is what drives Emily’s next big goal – advocacy. The state of Massachusetts is one of only two states (the other being California) that provides a financial safety net for retired boxers. “A big goal of mine is to continue to try to make sure that these fighters have access to funding from the state or that there’s some kind of organization for these fighters.”

On the Legacy of Her Work

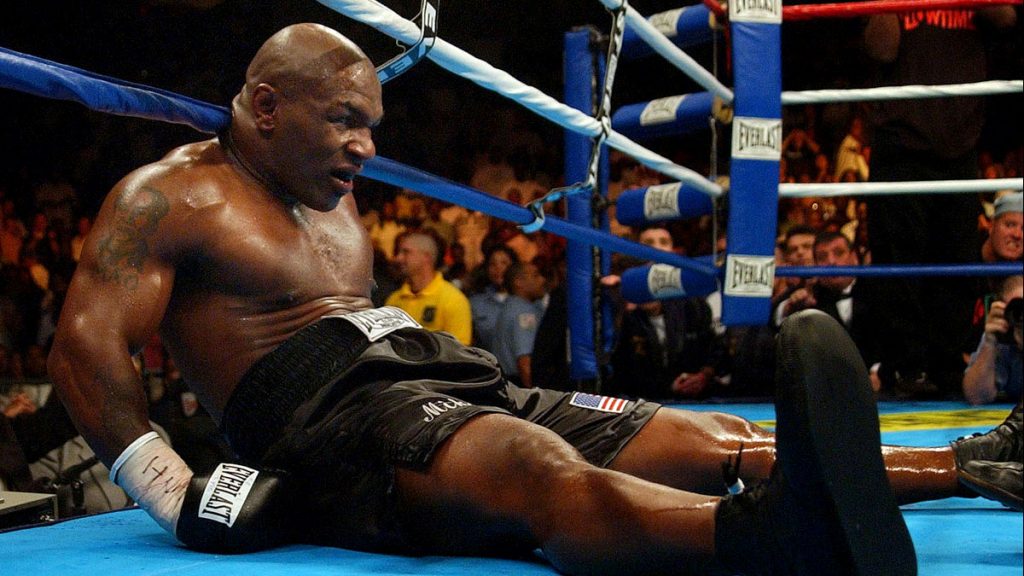

Emily teaches photography at a local high school where she is introducing a whole new generation of budding artists to boxing. She continues to work as a professional boxing photographer. One of her favorite pieces is a photograph of Mike Tyson after he was knocked down by Kevin McBride. “It’s special to me because when I first started covering boxing, he [Tyson] had retired. So, I never thought in my wildest dreams I’d ever get to photograph him. And I never also thought that the guy I was working for would actually beat him.”

When asked what she wants the conversation to be around her body of work, she immediately goes back to those early days.

“When I first started, I was the only woman covering boxing on a regular basis. There were two other women who would cover boxing in their area, but they wouldn’t go anywhere, and they weren’t publishing anywhere beyond the one person they were working for.

“I remember being in Atlantic City and being removed from ringside. So, I always had to watch what I did and what I said, because I felt like at any point somebody could say, ‘Get rid of her because she’s the distraction.’ I was the lone female, in a lot of cases. I think that came from going up watching some boxing reporters who were female being pushed to the wayside. So, in some respects, I want my work to be known as one of the females who opened the door for other women to cover the sport.” You can find Emily’s work on Instagram @the_emily_harney, or visit her website at Fightography.com.