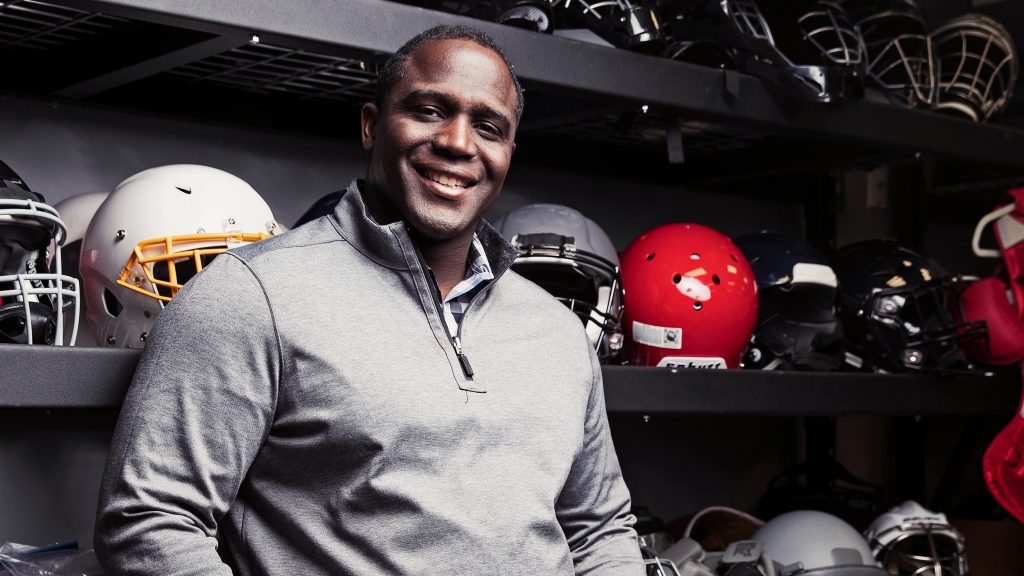

Former NFL Pro-Bowler Shawn Springs is making a big impact on impact protection

It was the summer of 2012 when 13-year NFL cornerback Shawn Springs was driving up Interstate 95 south of Washington, D.C. with all three of his sons in the back seat. Teenage twins Skylar and Samari were belted in, and young Shawn, just 5 years old at the time, was in his car seat. Springs’ Cadillac Escalade struck a driver who had stopped in the middle of the freeway, totaling the vehicle. But all four Springs men, including little Shawn, were fine.

“It’s about doing something that can make a difference in the world.“

Shawn Springs

Springs had gotten his son’s car seat from Ken Duffy, an executive at the child safety company Dorel Juvenile Safety 1st, whom he met in Washington while with the Redskins. Even before the accident, Springs had been interested in the technology inside the baby seat; if the cushioning inside the seat could protect a baby’s head during a collision at 40 miles per hour, it stood to reason it could also protect a football player’s head from impact. Isn’t football, after all, a series of car crashes? But the baby seat’s padding was much softer and more pliable than that in a football helmet. Springs was intrigued, and founded Windpact in 2011. Now, the company has raised nearly $6 Million, is about to close its series seed round of fundraising, and will follow soon after with a Series A.

Springs goal is simple: To build the most advanced impact-protection company in the world. And he’s well on his way.

“When Shawny walked away from that accident virtually unscathed, it solidified Shawn’s determination to push forward with adapting the technology for football helmets and beyond,” says Windpact chief of staff Kaarta Maron. “The accident was a game-changing moment for Shawn. It really sealed his mission.”

Really, though, it started long before the car seat. In 1997, when Springs was drafted, third overall, by the Seattle Seahawks, Microsoft founder Paul Allen owned the team. Throughout Springs seven years in Seattle, Allen fostered Springs’ interest in business, science and technology and encouraged his entrepreneurial spirit. “Mr. Allen taught me it wasn’t just about being a billionaire,” Springs says. “It’s about doing something that can make a difference in the world.”

Maron met Springs when he was playing for the Seahawks and she was in their community relations department. Springs was always community minded and interested in charitable endeavors, so Maron helped him start his Springs for Life foundation, then followed him East when he started playing for the Redskins in 2004. “Who Shawn is, and his enthusiasm for learning and helping others and making a difference, is what made me want to work with him,” Maron says. “He has so many ideas and he is always able to figure out how to get them done.”

While in the NFL, Springs, a defensive back who took more than his fair share of bumps to the head, wondered why the helmet his father, Ron Springs, wore in 1981 when he tallied 12 touchdowns for the Dallas Cowboys, looked pretty much the same as the one he was wearing 30 years later.

“If you look at a Honda or a Mercedes from 30 years ago, you wouldn’t recognize it with all the safety features and upgrades,” Springs says. “I wanted to know why helmet technology hadn’t really changed at all over that same period of time.”

Springs discovered three reasons the helmet industry hadn’t changed. First, no one, including the NFL, had any idea of the danger posed by both concussions and smaller, repeated blows to the head. Second, even when research began to emerge proving that danger, no one took it seriously until TIME Magazine put a worn, deflated football on the cover, along with the headline “The Most Dangerous Game.” And third, there has always been a large disconnect between helmet manufacturers and doctors.

Springs wanted to change all that. He gradually assembled a team of scientists, engineers and industrial designers to adapt the technology in the baby seat for other uses. At the time, Dorel was a $3 billion company and Windpact was just a startup, but Dorel’s patent was so specific, and the company had no interest in diversifying, that Springs had no problem getting a patent of his own. In 2013, Springs took his first prototype helmet to the Helmet Lab at Virginia Tech University, where it tested higher than any other helmet had tested to date. “That’s when we knew it would work,” says Maron.

The protective material in a standard football helmet is a single piece of hard foam that compresses to absorb impact over the distance between the shell of the helmet and the head. This is very effective for high-level impacts, but not very effective for lower-level impacts; hard foams protect you from cracking your skull on a big impact, but with softer impacts, they transfer the impact from the shell to the head too quickly to provide protection.

“I wanted to know why helmet technology hadn’t really changed at all.”

Shawn Springs

Windpact’s Crash Cloud technology, however, is designed to protect the head during all types of impacts. Crash Cloud is an air-diffused impact system composed of soft foam “air” bags that respond instantly to linear, angular and rotational impacts, wind springs that disperse energy through air vents upon impact, and refresh vents that rapidly reinflate each Crash Cloud to withstand the multiple impacts that often make up a single event.

“My main motivation is making the game safer for the next generation of athletes.”

Shawn Springs

“Our system tunes itself to the level of impact,” says Windpact director of design and development Leon Marucchi. “With a smaller impact, it is soft and compliant and will squeeze slowly and protect with great comfort. But if it’s hit hard, the system stiffens and locks up because the air cannot escape fast enough. It’s soft when it responds to smaller impacts and stiff when it responds to bigger impacts. It is self adjusting.”

In 2018, through the NFL’s HeadHealthTECH II Challenge, Windpact partnered with Riddell on its Speedflex Precision helmet and brought it up from No. 18 to No. 3 on the NFL’s Helmet Laboratory Testing Performance Results list, which evaluates which helmets best reduce head impact severity; Riddell chose to move forward with its own padding solution. Last April, Windpact won the NFL’s HeadHealthTECH VI Challenge, marking the third time the company has taken home an award from the League. This time, they are working with Schutt Sports on its Q11 helmet, which should be available for testing this spring.

Windpact is currently in the process of applying for the NFL’s Helmet Challenge, through which up to $2 million in HeadHealthTECH grant funding will be available.

“My main motivation is making the game safer for the next generation of athletes,” Springs says. “I have kids. My sons want to play, and I want to make sure the game is safer. I think we all want to make sure the game we love so much is not as dangerous and is safe for the next generation of athlete.”

Springs, though, will not stop at just football helmets. Windpact technology is currently available in a girls’ lacrosse helmet manufactured by Hummingbird Sports. It is being used in catchers’ masks made by Under Armour. And in 2018, Windpact was one of several companies given a contract by the Department of Defense to improve the Advanced Combat Helmet, or ACH. They were the only team that passed the 17 meters-per-second drop test (current helmets solve only for 10 MPS) and were awarded a second year of contract to improve the Enhanced Combat Helmet, or ECH; Windpact is currently building 80 prototypes.

“Our system tunes itself to the level of impact.”

Shawn Springs

Windpact has a proprietary database of characterized foams, allowing them to evaluate different types of materials, choose those for optimal performance and tune and build a Crash Cloud system to solve for any type of impact. It is currently being tested in gun butts for shot guns, wall pads for gymnastics and basketball, hockey boards and gloves, bicycle and motorcycle helmets, medical-grade protective pads for hip replacement surgeries, packaging for trucking and shipping and headrests and door panels in cars, amongst other things.

“It’s all just a matter of what kind of impact you need to solve for,” Springs says. “A headliner for an automobile is no different than a wall panel in the school gym. It’s just a matter of creating a precise solution for each specific type of impact.”

And having a serious impact on upgraded impact protection in the process.